Engineers Without Borders

My journey into Engineers Without Borders Australia was very sudden and unexpected. Towards the end of 2015, I was finishing up my third year of university and was looking for any opportunity to gain practical work experience in the field (which at the time I needed in order to graduate). Eventually, I was accepted into a 2 month internship based in a Hangzhou, China, with a state owned corporation called the China Huadian Electric Power Research Institute. I would be lying if I said that this first work placement was anything less than transformative. It was my first time working within a large organisation, overseas in China with its own unique set of societal expectations and behaviours and I was also technically working as an (undergraduate) engineer! It was an incredibly exciting international adventure and an intensive personal and professional learning experience at the same time.

One of my key takeaways would have to be the entire experience of living like a local in China, an upcoming global superpower and the world's factory, on a longer term than just a short visit. While based in Hangzhou, my two buddies and I were able to spend the weekends by travelling to Shanghai which was only a few hours away by train as well as further North to Beijing for the Great Wall and inland to Xi'an where we saw the famous Terracotta warriors. As the saying goes, time flies when you are having fun and the two months of living in China came to an end before I even expected it.

Photo credit: Julian Goh, 2016

It was around the same time when I landed the work opportunity in China that I stumbled upon a program called the 'Engineers Without Borders Humanitarian Design Summit' that was being held in Cambodia from early February 2016 for two weeks, coinciding with the end of my China internship. The promotional material claimed that participants would have real world experience of delivering social change through engineering and experience full immersion with a local community in Cambodia - all of which appealed to my taste for adventure and interest in using engineering as a tool to deliver value in the world. So I signed up for it on the spot, taking out a government loan to fund the hefty price tag, and soon I was ready and excited to take on the adventure.

Photo credit: Thomas Harvey, 2016

When I left China early in February 2016, I found myself in a plane headed directly for Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where I was scheduled to start the Humanitarian Design Summit with Engineers Without Borders immediately. Unlike the other participants, who were headed North from warm and sunny Australia with thongs and t-shirts in tow, I was headed South with heavy bags full of winter gear. When I arrived in the airport late at night, I was greeted immediately by the heat and humidity but also by the warm welcome by one of the program facilitators, Ben, and we rode along in a Tuk Tuk all the way to our accomodation for the rest of the week in Central Phnom Penh.

The first few days flew by with workshops, group ice breakers, delicious food and preparation for the time we would spend further North away from the capital city and with the local communities. There were about 50 participants in this February program and within the first few hours of being with the group, I felt at ease very quickly. It was very easy to strike up a conversation with most of the individuals in the group, who all shared similar educational backgrounds and expectations from being on the Design Summit. Soon enough, I also found numerous individuals who inspired me to be more and do more in life through their incredibly interesting stories of pre-Cambodia trekking in the mountains of Nepal, amazing plans of further travels in Vietnam after the Summit and the hobbies they got up to back at home. I had found my tribe.

“ ... all of which appealed to my taste for adventure and interest in using engineering as a tool to deliver value in the world. ”

By mid-week, we travelled North by bus to a small town called Kratie (pronounced Kra-Cheh) which was our base for the rest of the program. From here, we would travel by boat to the local communities who lived off the mainland on smaller and isolated islands. The big group of 50 was soon split into more manegeable clusters of about 15 - 17 people with the three teams being Team Ibis, Team Banana and Team Turtle. We also heard firsthand from Cambodian Rural Development Team (CRDT) representatives, the organisation that EWB works in partnership with in the region. CRDT are a local non-for-profit organisation based in Kratie aimed at lifting Cambodian communities out of poverty and to support environmental conservation - a crucial cog in the wheel that enabled our immersion time with the rural communities.

Photo credit: Tom Harvey, 2016

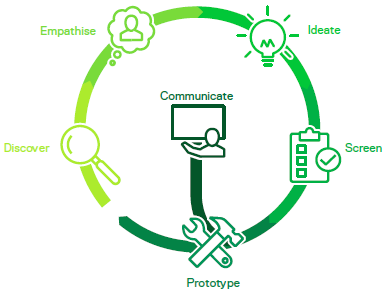

Soon enough, the rest of Team Banana and I found ourselves on small motorised canoes headed towards the rural village of Koh Dambang where we would be living with the community, sharing food and living spaces and getting a feel of what it was like to walk in their shoes. This complete immersion was the first necessary step in the 'Discover' phase of the Human Centred Design process which we were just about to start.

Photo credit: Engineers Without Borders Australia, 2016

When we found a place to store our bags, a roof to sleep under and felt settled into the community, we spent the first few days on Koh Dambang in 'Discovery' which involved learning the development context, how the Human Centred Design cycle works and building the foundations of our knowledge base. By spending time within the local community, we were then able to commence the Empathy stage where we were able to get a sense of their daily lives, how they worked to earn a living, the values they had and the challenges they faced on a daily basis. This approach of starting conversations with the people we were designing for, of having a two way sharing of knowledge and putting people first, meant putting faith in the design cycle and not starting the journey by implementing designs based on our own preconceptions.

It was scary at first but by asking questions, we were not seeking to confirm our own biases and ideas but instead to start off with a 'beginner's mind', which was to approach the task as a novice even if you already know a lot about them. This mindset allowed us to be eager to learn and willing to experiment which positioned us well in developing solutions that were more appropriate to the end user. In hindsight, it was surprising to learn that the stakeholders who we were hoping to design solutions for often had effective, practical and sustainable answers to their own problems and we were there simply as facilitators to this journey.

Photo credit: Julian Goh, 2016

“ This approach of starting conversations with the people we were designing for, of having a two way sharing of knowledge and putting people first, meant putting faith in the design cycle and not starting the journey by implementing designs based on our own preconceptions. ”

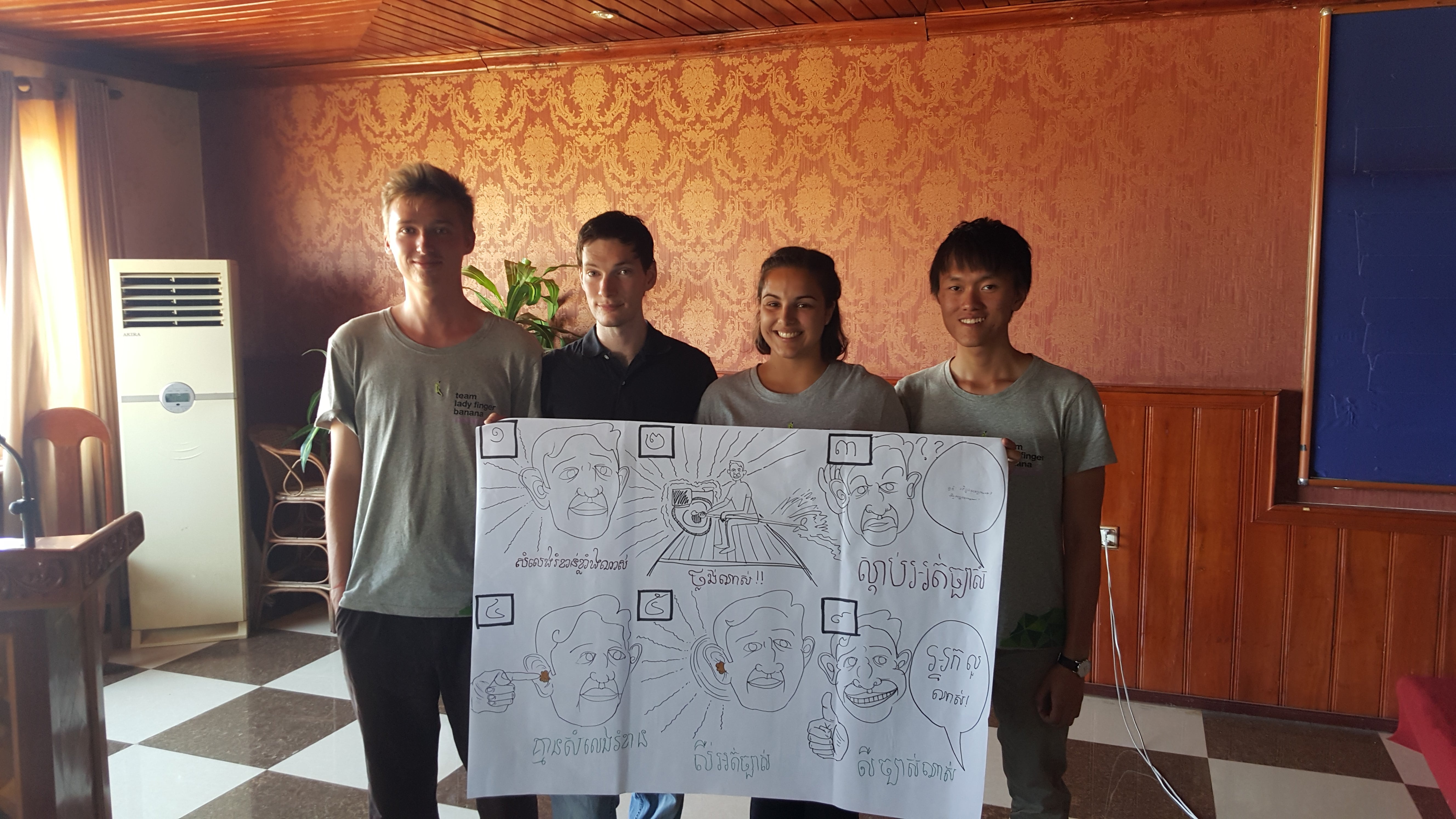

After Empathy, the stage was set to begin Ideation and Prototyping where we would share ideas, and brainstorm among small teams of 4 - 5 to design as well as build new products, services or processes to support the commmunity. Key areas that we developed as a collective Team focused on hearing protection education, ergonomic agricultural tools and improved farming processes.

Choosing a specific design challenge was not an easy process and there was a strong focus on 'failing fast'. The idea being that the Human Centred Design process was not linear and re-iteration between Empathy, Ideate and Prototype was not unexpected - the more you failed early in the process the more appropriate and sustainable your final product will be. My team also had a situation where members within my team were divided between hearing protection education and an improved wheat planting tool, with my personal preference being the former. The majority of the team were leaning towards the agricultural tool because it meant that the prototyping stage would end up producing a tangible solution that we could then present back to the community.

I soon realised an idea that would tip the scales, which was an observation that most of the other groups within Team Banana were also addressing the agricultural concerns. I made the decision to pitch this to the team and in the end, through some negotation and mentoring from our supervisor Ben, we were able to settle for developing the education program for the reason that it would add the most value to the overall vision of the Design Summit - which was to generate as much ideas and solutions for CRDT to implement in the rural communities they were trying to assist in the long term. On top of that, we were still able to contribute the design ideas we had developed for the agiricultural tool towards another groups within Team Banana which ended with a win-win for all of us.

Photo credit: Julian Goh, 2016

From the entire two weeks I spent in Cambodia, my key takeaway was having a deeper understanding of how a fundamental part of developing an appropriate and sustainable engineering solution was to first listen and learn from what the end users had to share before we could start applying our engineering skills and knowledge. It would have been easy to come in, especially from a technical engineering background, ask a few questions to confirm pre-conceptions and assumptions and then implement technical solutions that I personally thought would be appropriate but was not actually effective in addressing the issue. This was an interesting reflection I made as I was going through the rounds of the Human Centred Design process and it really made me think about my mindset and how my engineering background positioned me to start addressing the challenges that were evident to me, which might not actually be an accurate representation of the root challenges the community was facing.

This was also very different to the approach that university had equipped me with prior to the Summit, which was to receive a set of problems and to go about solving it by reaching certain specifications of production output or product quality, without ever considering the needs of people and of an end user. A human centred, people first approach, together with the focus on working with the strengths of the community (looking at what they already had or were already doing and building upon that rather than focusing on what is missing and reinventing the wheel) and having two way conversations to share knowledge were the three incredibly important lessons I took away from the Design Summit.

Looking at the next steps of my engineering career and what a humanitarian career would look like, I remember reflecting on my pre-Summit concerns of how having a lack of technical experience would mean an encumbered ability to deliver solutions for social change through engineering and how after my two week experience in Cambodia my concerns were no longer as intimidating. The Design Summit was an incredible and intensive learning experience that has empowered me to understand the powerful social impact that engineers can make on the world.

Photo credit: Thomas Harvey, 2016

When I returned home, I was fueled with inspiration to make positive change. What better place to start than with the local communities I lived within. I immediately got actively involved with the Engineers Without Borders Chapter we have here in Western Australia, where I stumbled upon the Spokes in the Wheel program which was the perfect fit for me. Not only have bikes been an integral part of my personal life but it also resonated with what I wanted to achieve in helping the wider community. The Spokes in the Wheel initiative was and is currently a program designed to educate kids about bike fixing techniques, fundamental riding skills and most importantly, road safety. The Spokes program is currently being run with a local community partner organisation called Sudanese Autralian Integrated Learning (SAIL) who are a national organisation providing Sudanese refugees and migrants with access to free tutoring services. The Spokes program seeks to compliment SAIL's committment to the Sudanese community by providing access to bicycles and to the wider engineering community here in Perth.

“ The Design Summit was an incredible and intensive learning experience that has empowered me to understand the powerful social impact that engineers can make on the world. ”